You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Legislation’ category.

Can We Still Keep Wilderness Wild?

by Louise Lasley

Most of us probably believe we can correctly figure out fact from fiction, good from bad, and many other distinctions we make every day. But sometimes our perceptions are forged by subtle, if inadvertent, messages we receive. And before long the collective perspective becomes our culture with an almost unobservable change in what is believed to be right or good or necessary. This shift from original intent to accepted practices applies to our best-protected lands and threatens not only designated Wilderness, but the Wilderness Act, too.

Most of us probably believe we can correctly figure out fact from fiction, good from bad, and many other distinctions we make every day. But sometimes our perceptions are forged by subtle, if inadvertent, messages we receive. And before long the collective perspective becomes our culture with an almost unobservable change in what is believed to be right or good or necessary. This shift from original intent to accepted practices applies to our best-protected lands and threatens not only designated Wilderness, but the Wilderness Act, too.

I recently received information on an upcoming wilderness festival, and the first thing that caught my attention was the phrase: “management is a necessary part of our interaction with this resource” (meaning Wilderness). I count this as one of those subtle messages that tend to shift behavior. To manage something is a dynamic, manipulative action that implies human intervention and control. The responsibility of the four federal agencies that oversee Wilderness is to administer these lands using a hands-off approach rather than manage them. Congress and the American people have set aside Wilderness to allow nature to call the shots.

The Wilderness Act defines Wilderness as, “…an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Howard Zahniser explained in a 1957 speech the intended meaning of “untrammeled” as “free, unbound, unhampered, unchecked, having the freedom of the wilderness.”

Stewart Brandborg worked closely with Zahniser on the Wilderness Act, and then served as executive director of the Wilderness Society for 12 years after the law’s 1964 passage. These two roles created millions of acres of designated Wilderness. The late Bill Worf, a former Forest Service (FS) supervisor and fierce advocate for Wilderness, was part of a small group tasked with writing the FS regulations for the Wilderness Act. For years these two men were the backbone of Wilderness Watch, the only national organization working exclusively to assure that Wilderness is administered according to the law. Neither would stray from their conviction that the Act does not allow for compromise nor should it be subject to individual interpretation.

I can’t tell you when the shift from the original intent for stewardship of these lands began, but it has been moving a lot. The other night at dinner Stewart Brandborg said that the next presentation regarding Wilderness should be titled: “It’s all Screwed Up.” Here are a few examples of how the law is being disregarded:

- A private company used a helicopter to haul materials to repair the Fred Burr High Lake dam in the Montana portion of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, even though in the past materials were carried in by packstock or found onsite.

- A proposed road would cut through the Izembek Wilderness in Alaska.

- In the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in Minnesota, commercial towboat traffic has increased significantly instead of maintaining levels existing at the time of designation.

- There is a proposal to considerably expand the Fish Lake airstrip in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness in Idaho.

- In the Emigrant Wilderness in California, buildings have been rebuilt and commercial packstations exceed historical numbers.

- Commercial shellfishing is occurring in the Monomoy Wilderness in Massachusetts.

- 450 Helicopter landings have been proposed for bighorn management in Wildernesses in Arizona.

- Motorized cattle herding has been proposed in Wildernesses in the Owyhee region of Idaho.

- Water developments have been built in the Kofa Wilderness in Arizona, using construction equipment and helicopters.

- Unnecessary structures have been restored and rebuilt in the Olympic Wilderness in Washington.

- And on and on…

Such illegal actions were probably considered acceptable by the agencies, weren’t that much different than some earlier action, or would help with an issue unrelated to Wilderness. Or as my friend Howie says, “They have landscape amnesia.” In other words, they’ve forgotten what Wilderness is supposed to be. All illegal actions are damaging to Wilderness, but cumulatively they amount to a “death by a thousand cuts,” with incremental changes sometimes only obvious over longer periods of time.

How did we get to this place? Who is responsible? Often, agency employees notify Wilderness Watch of violations occurring in Wilderness. The most abused part of the Wilderness Act is the administrative exception in section 4(c), which allows the minimal action necessary to administer the Act. It was intended to apply to those exceedingly rare instances where motorized equipment, motor vehicles, aircraft, structures or installations are truly necessary and constitute the absolute minimum required to preserve Wilderness. Instead, the agencies increasingly invoke the exception whenever it is convenient or to promote recreation or one of the other uses of Wilderness. Unfortunately, many of these violations provide the jumping-off step for the next, bigger illegal action.

The U.S. Forest Service, the National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have a long history of resisting the Wilderness Act. But it is not just the agencies that have dropped the ball. Congress has failed in its oversight of the agencies and its review of the state of the Wilderness system. A 1989 Government Accounting Office (GAO) report requested by the House Subcommittee on National Parks and Public Lands found that the Forest Service was “devoting only minimal attention to wilderness,” but nothing came of the report’s recommendations to prevent further degradation of Wilderness. In 1995, Congress passed the Paperwork Reduction Act, which rescinded a provision of the Wilderness Act that required the agencies to submit substantive annual reports to Congress on the state of the Wilderness system. And in perhaps the most alarming assessment of the Wilderness system, a 2001 report by the Pinchot Institute for Conservation warned, “The four wilderness agencies and their leaders must make a strong commitment to wilderness stewardship before the Wilderness System is lost.” Yet neither Congress nor the agencies have made any meaningful actions to address the recommendations of this in-depth, comprehensive report. It is now largely forgotten.

Current stewardship oversight, or lack thereof, is only part of the degradation of Wilderness by Congress. Congress is proposing bills as damaging to Wilderness as the violations the agencies are carrying out—and maybe more so. Bills designating Wilderness in the past were clear and simple and adhered to the Act. Increasingly, wilderness bills include exceptions not in the Act, have language that undercuts the Act, or add damaging non-conformities to both existing and proposed Wildernesses. The current Congress includes 51 such bills. , Many of the proposed bills are supported by the larger conservation organizations, who, because of their size, proximity to DC, and their budgets, have usurped negotiations from local organizations who are working to designate additional Wilderness. These larger organizations who claim that compromise is necessary to gain more public support, along with Congress, are making the Wilderness Act into something other than what was envisioned during its long and inclusive passage into law.

So whose responsibility is it to ensure that Wilderness retains the character that makes it wild, that ours and future generations are able to experience the wild, and that accountability for wilderness is acknowledged and accepted? I believe this responsibility belongs to Congress, to the four administering agencies, and finally to us—the “public”, the folks who know the wilderness lands around them, cherish their unique and special qualities, and are grateful for what Wildernesses don’t have: those activities that would make a Wilderness just the same as any other place. The question remains, can we still keep Wilderness wild in the face of so many challenges to the Act’s original intent?

Louise Lasley’s (president of Wilderness Watch) pursuit of backcountry activities produced a strong advocacy for wilderness and the values we find in wild places. She has worked for years to protect those values around the globe and particularly within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Work on public lands and wildlife issues for the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance, Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative, the Wildlife Conservation Society, Africa Rainforest and River Conservation, and as a naturalist for the Bridger-Teton National Forest and Spring Creek Resort has been fundamental to her new endeavor to look at local issues as she travels around the West. After living in Jackson Hole for 30 years, Louise began the life of a gypsy this year looking for a someplace to call home. She hopes that her knowledge and experience of public lands and wildlife concerns will help in her transition to a new community.

Paddling would mar wild landscapes

By Franz Camenzind

For the second time in as many years, a bill that would open certain waterways within Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks to “hand-propelled vessels” is making its way through the legislative maze in Washington, D.C. Introduced by Congressman Cynthia Lummis and pushed by the kayaking and packrafting community, the new law is aimed at granting this single user group access to more front- and backcountry waterways in our two national parks. As written this bill directs “the Secretary of Interior to promulgate [to proclaim formally or put into operation] regulations to allow the use of hand-propelled vessels on certain rivers and streams” in the two parks.

For the second time in as many years, a bill that would open certain waterways within Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks to “hand-propelled vessels” is making its way through the legislative maze in Washington, D.C. Introduced by Congressman Cynthia Lummis and pushed by the kayaking and packrafting community, the new law is aimed at granting this single user group access to more front- and backcountry waterways in our two national parks. As written this bill directs “the Secretary of Interior to promulgate [to proclaim formally or put into operation] regulations to allow the use of hand-propelled vessels on certain rivers and streams” in the two parks.

Instead of having our park’s waterways managed by resource professionals abiding by the service’s Organic Act, this bill would set as policy the desires of a special interest group teamed with Washington politicians. This is a terrible way to manage our national parks.

A leading force behind this legislation is the Jackson-based American Packrafting Association. Its website presents a list of rivers and streams it wants studied for floating — 39 in Yellowstone and 13 in Grand Teton, totaling 475.2 miles. Included are portions of the Gros Ventre River (the park-elk refuge section), Cottonwood, Ditch, Spread, Pacific, Pilgrim and Lake creeks, and parts of the Firehole, Madison, Gallatin, Gardner, Lamar, Lewis, Nez Perce, Pebble and Slough creeks in Yellowstone. A singular (unwritten) goal of APA is to gain access to the 36-mile stretch of the Yellowstone between Seven Mile Hole (a few miles below the Lower Falls) and Gardner, with the grand prize being the 20-mile segment known as the Black Canyon.

If these streams are opened to whitewater adventuring, iconic vistas enjoyed by millions of visitors each year will no longer seem wild and untouched. Instead, visitors will be distracted by scenes of florescent technology cutting through the heart of some of our nation’s most treasured landscapes. Gone will be that glimpse of what primitive America looked like when the land was untouched and imaginations were free to contemplate creation’s many wonders. Tranquility and the ability to be inspired by wild, uncluttered vistas are values worthy of protection, too. These are values cherished by millions of visitors each year. Values worth protecting for all future generations. So much would be forever lost if packrafting, kayaking and floating were allowed on these few, last free-flowing waterways. And all because one special interest group wanted another adventure-filled playground.

Proponents argue that this law will only cause the parks to “study the feasibility” of floating select streams, and that this study needs to occur because this issue has not yet been properly analyzed. Both assertions are false. As written, the bill would require the parks to divert their under-staffed management teams away from day-to-day park operations and have them conduct an expensive NEPA analysis of all floatable rivers and streams within their jurisdiction, and to create regulations allowing certain streams to be opened to floating. The APA claims that it only wants 42 “select” waterways studied. A NEPA process would likely require that all major floatable segments and all types of floating devices be analyzed. APA does not control how NEPA works.

In part because of heavy pressure from a few individuals in the late 20th century, Yellowstone officials conducted a NEPA analysis of this very issue. The document signed in 1988 recommended that: “Due to the high level of potential impact that river boating has on the biophysical environment of Yellowstone National Park, the No Boating/No Action alternative is recommended.” The recommendation was based in part on the fact that abundant whitewater opportunities occur outside the park. Apparently APA has chosen to ignore the previous findings and that the study even occurred.

Every time we extend our self-indulgent and technologically enhanced desires deeper into the backcountry — whether it be opening waterways to kayaking, carving turns in remote backcountry or paving trails through rich wildlife habitat — we force wildlife into smaller corners of our remaining undisturbed lands. How many times, how many ways can we keep squeezing our wildlife and still hope to have sustainable populations? Our stewardship responsibilities demand that we examine our actions and impacts generations into the future. Not just for our benefit but, for the future of the land and the wildlife it is home to.

There is no other Greater Yellowstone. Our parks should be the most protected and most intact parts of this greater landscape. They should not become pleasuring grounds for a select group of adventure seekers wanting to push their new technologies deeper into our wildlands. Why is it that we seem to want to conquer everything like dogs running feral across the landscape? Can we not leave a few of our planet’s remaining treasures free from change?

Conservation has its deepest meaning when motivated by selfless altruism, not special interest desires.

———————————-

Dr. Franz Camenzind is a wildlife biologist turned filmmaker and environmental activist. In his career he conducted numerous wildlife assessments, often focusing on threatened and endangered species. Serendipitous opportunities lead him to a long career in the documentary film industry where he produced films on coyotes, wolves, grizzly bears, pronghorn antelope, giant pandas and black rhinos. Although now enjoying retirement in his Jackson, Wyoming home of 44 years, he is still very much involved in local, regional and national environmental issues. He spent his last 13 years as Executive Director of the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance. Prior to that he served on its board for 13 years and was one of the founding board members of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition. Dr. Camenzind serves on Wilderness Watch‘s board of directors.

Wilderness: The Next 50 Years?

By: Martin Nie and Christopher Barns

By: Martin Nie and Christopher Barns

September 3, 2014 commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the Wilderness Act of 1964. No other environmental law, save perhaps the Endangered Species Act, so clearly articulates an environmental ethic and sense of humility. The system the law created is like no other in the United States. Once designated by Congress, a wilderness area is to be managed to preserve its wildness, meaning that these special places are to be free from human control, manipulation, and commercial exploitation.

Celebrations are being planned throughout the country and each will undoubtedly take a look back at the history of this law and the land it now protects. But what is the future of the wilderness system?

The story of wilderness is far from finished. Most at stake are lands managed by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) and Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Both agencies manage millions of acres that are potentially suitable for wilderness designation. For the USFS, this includes land that is currently managed pursuant to the 2001 roadless rule (35.7 to 45 million acres depending on the inclusion of the ever-contested Tongass National Forest), and state-specific roadless rules covering Idaho (9.3 million acres) and Colorado (4.2 million acres). Also at stake are wilderness study areas (3.2 million acres) and places recommended for wilderness designation by the agency itself (5 million acres).

The BLM manages 528 Wilderness Study Areas (WSAs) totaling approximately 12.8 million acres, most of which were identified in the initial BLM inventory of its lands in the late 1970s. The agency is currently updating its inventory of other areas with wilderness characteristics, and a very rough estimate is that an additional 5 to 10 million acres will be identified – not including Alaska. The first inventory for areas with wilderness characteristics on lands managed by the BLM in Alaska has started, and perhaps 40 million acres will be found.

These lands provide the base from which future wilderness designations on USFS and BLM lands may come. Complicated planning processes, interim management measures, and politics will ultimately determine whether or not these lands are protected in some form in the future. The politics of wilderness is more complicated and challenging in 2014 than it was in 1964. We believe that three interrelated factors will shape wilderness designations in the future: extreme political polarization, trends in collaboration, and increasing demands for the manipulation of wilderness.

Congressional Polarization

We begin by focusing on the increasing polarization of Congress and its impact on wilderness politics. Since the Wilderness Act requires an act of Congress to designate wilderness, what happens in this institution necessarily impacts what happens to wilderness-eligible lands.

The history of the Wilderness Act makes clear that Congressional partisanship and ideology have always factored into wilderness politics. After all, Congress considered some 65 versions of the law over an eight-year political process. Politics notwithstanding, the U.S. House of Representative still passed the law by a vote of 374 to 1, and in the previous year, the U.S. Senate passed a version of the Act by a 73 to 12 margin.

What has so remarkably changed since these votes is the degree of partisan and ideological polarization of Congress. The so-called “orgy of consensus” that ostensibly characterized the environmental lawmaking of the 1960s and 1970s has all but disappeared in a loud and angry falling out of the center.

Political scientists show the extent to which the parties have polarized, or become more ideologically consistent and distinct, since the 1970s. A drastic homogenization and pulling apart of the parties is evident. A task force convened by the American Political Science Association shows there to be a major “partisan asymmetry in polarization.” According to the authors, “Despite the widespread belief that both parties have moved to the extremes, the movement of the Republican Party to the right accounts for most of the divergence between the two parties.”

Polarization has already impacted wilderness politics. For example, the 112th Congress was the only Congress to actually decrease the size of the Wilderness System. And we cannot recall a House session that has introduced or passed so much anti-wilderness legislation.

There is little reason to believe that polarization will abate any time soon so chances are good that gridlock and dysfunction will characterize wilderness politics, as it does in so many other policy areas. Designations will become more difficult and those opposing them will ask for a more absurd list of political concessions. If legislative channels remain blocked, we also suspect that a wilderness-friendly President will take more protective actions in the future, such as using Executive powers to withdraw lands from mineral development or by using the Antiquities Act to designate national monuments.

Compromise and Collaboration

Some wilderness advocates have embraced more collaborative approaches to wilderness politics, an approach whereby those seeking additional wilderness make deals with an assortment of interests that want something else, from rural economic development to motorized recreation. While collaboration could potentially break long-time wilderness stalemates, we fear that those collaborating in today’s polarized political context may make deals that collectively threaten the integrity of the Wilderness System.

The move towards collaboration in contemporary wilderness politics is understandable for a couple of reasons. First is the nature of the remaining wilderness-eligible lands managed by the USFS and BLM. Many wilderness battles of the past were focused on protecting “rocks and ice,” high altitude alpine environments with fewer pre-existing uses than found on lower elevation lands. But many current wilderness proposals now aim to protect lower elevation landscapes—and thus places with more “historic” uses and entrenched interests associated with them. The growing use of motorized recreation also helps us appreciate why some wilderness advocates have a sense of urgency when it comes to making deals to get wilderness designated sooner rather than later. Wilderness advocates fear that these machines will increasingly intrude into potential wilderness areas and make their protection more difficult in the future because of associated impairments and claims of “historic use.”

That compromise is part of wilderness, as it is for politics more generally, is not the dispute. What is disputed is whether these compromises have gone too far in recent years and what precedent they set for the future of the Wilderness System. We suspect that multi-faceted negotiations, in which wilderness is but one part of larger deals, will increase in scale and complexity. Wilderness may become currency in lop-sided negotiations—providing something to trade in return for more certain economic development on non-wilderness federal lands.

We are also concerned that those interests collaborating will view the original 1964 law as simply a starting point for negotiations and that there will be increasing calls for non-conforming uses and special provisions in newly-designated wilderness areas, such as language pertaining to grazing, wildlife management, motorized use, and fire. Precedent is a special concern in this context because of how often special provisions—to meet the desires of those opposed to wilderness—are replicated in subsequent wilderness laws. There appears to be a disturbing trend in the collaborators representing “conservation” interests negotiating away central tenets of the Wilderness Act in exchange for simply getting an area called “Wilderness” designated. As a result, recent legislation appears to be enshrining the WINO – Wilderness In Name Only.

Wilderness Manipulation

The third issue pertains to what we believe will be increasing demands to control and manipulate wilderness in contravention of the law’s mandate to preserve wilderness areas as “untrammeled.” Such demands will likely be made in the context of ecological restoration and efforts to mitigate and adapt to various environmental changes, such as threats posed by climate change. We suspect that future wilderness designations and the politics surrounding them will increasingly use climate change—whether as a legitimate concern, or merely an excuse—to focus on issues such as water supply, fire, insects, disease, and invasive species.

The relationship between water and wilderness will be particularly problematic in the West. Testifying before Congress on the proposed San Juan Mountains Wilderness Act of 2011, the USFS shocked many by opposing the bill’s provision to prohibit new water development projects in the new wilderness areas.

The water issue is also likely to manifest itself through the artificial delivery of water to wildlife populations in wilderness. The USFWS acquiesced to the state of Arizona’s request to build two artificial wildlife waters to benefit bighorn sheep within the Kofa National Wildlife Refuge Wilderness, despite the presence of over 60 such installations already in the area. However, this decision to manipulate the wilderness ecosystem was contested, and in 2010 the Ninth Circuit ruled that the USFWS failed to adequately analyze whether these “guzzlers” were necessary to meet the law’s minimum requirements. It seems that the courts will defend the undeveloped nature of an untrammeled wilderness where the agency charged with its stewardship will not.

Recently introduced legislation goes even further – beyond simply providing artificial water: the Sportsmen’s Heritage Act of 2012 version that passed the House would guarantee that any action proposed by a state wildlife agency would automatically satisfy the “necessary to meet minimum requirements” test mandated by Section 4(c) of the Wilderness Act.

Manipulating wilderness ecosystems frequently involves placing structures or installations in areas that are, by law, supposed to be undeveloped. They may make the area less natural, even though the law requires wilderness to be “protected and managed to preserve its natural conditions.” And, uniformly, they manipulate areas “where the earth and its community of life are [supposed to be] untrammeled.” These demands may end up as bargaining chips in the designation process – part of the increase in collaboration and compromise that is the hallmark of recent legislation. Manipulating wilderness ecosystems, which now seems acceptable to some “conservation” interests, may become a de facto political requirement in an increasingly polarized political climate where it seems one side seems to not care how an area is managed as long as it’s called “Wilderness,” and the other side doesn’t care what it’s called as long as it’s not managed as wilderness.

So, is “Wilderness” an idea whose time has come and gone?

***

We reflect on the words used by Congress in establishing the Wilderness System in 1964:

In order to assure that an increasing population, accompanied by expanding settlement and growing mechanization, does not occupy and modify all areas within the United States and its possessions, leaving no lands designated for preservation and protection in their natural condition, it is hereby declared to be the policy of the Congress to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness.

The italicized words are emphasized because they explain why the reasons for adding to the Wilderness System are stronger in 2014 than they were fifty years ago. In 1964, the U.S. population was 192 million, it is now approaching more than 319 million. Along with this increasing population has come a staggering expansion of settlement, especially in the American West, and a phenomenal increase in the amount and power of motorized and mechanized use on public lands. The Wilderness System remains vital in protecting places and values that are increasingly rare in modern society.

Now, more than ever, we need the transcendent anchor provided by Wilderness. This is not asking for too much when we consider that roughly 5 percent of the entire U.S. is protected as wilderness, and a mere 2.7 percent when Alaska is removed from the equation. Nor is it too much when we consider that the majority of the U.S. has already been converted to agricultural and urban landscapes, with much of the remaining lands networked with roads. We are not so poor economically that we must exploit every last nook and cranny of our wild legacy for perceived gain; we are not yet so poor spiritually that we should willingly squander our birthright as Americans.

This is why we must fight for “Capital W” Wilderness, as originally envisioned, and make a stand for those last remaining roadless areas with wilderness characteristics that deserve our protection. It also means pushing back against the tide of compromising away the very essence of wilderness, and resisting the urge to manipulate wild places as if they were gardens to produce some desired future as if we knew what was always best for the land.

We need Wilderness, real Wilderness. Now, more than ever.

***

Martin Nie is Director of the Bolle Center for People & Forests at the University of Montana. Chris Barns is a BLM Wilderness Specialist in the National Landscape Conservation System Division, and that agency’s representative at the Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center. His contribution to this essay should not be taken as an official position of the Department of the Interior or BLM. The Article from which this essay stems was published by the Arizona Journal of Environmental Law & Policy in October of 2014. Click here to view.

Wilderness in the Eternity of the Future

By Ed Zahniser

*Editor’s note: The following is reprinted from a speech Ed Zahniser gave this past May in Schenectady, NY.

Ed Zahniser speaks at the Kelly Adirondack Center of Union College in Schenectady, NY, May 8, 2014. The Center includes the former home of Paul and Carolyn Schaefer and family. Photo: Dan Plumley, Adirondack Wild: Friends of the Forest Preserve.

My father Howard Zahniser, who died four months before the 1964 Wilderness Act became law 50 years ago this September 3, was the chief architect of, and lobbyist for, this landmark Act. The Act created our 109.5-million-acre National Wilderness Preservation System.

Had I another credential, it would be that Paul Schaefer—the indomitable Adirondack conservationist—was one of my chief mentors and outdoor role models. Paul helped me catch my first trout. I was seven years old. That life event took place in what is now the New York State-designated Siamese Ponds Wilderness Area in the Adirondacks. Izaak Walton should be so lucky.

I worked for Paul Schaefer’s construction outfit, Iroquois Hills, for two high school summers. I lived here in the family home—897 St. David’s Lane—along with three of Paul and Carolyn’s four children, Evelyn, Cub, and Monica, and Paul. I slept in the Adirondack room—in the loft. Carolyn Schaefer, Ma Schaefer, was cooking for the weather station on Whiteface Mountain those two summers. Evelyn and Monica and I were on our own in the kitchen with an oven that had just two settings, “off” and “hot as hell.”

I spent many of those summer weekends with Paul in his Adirondack cabin, the Beaver House, near Bakers Mills. It was his heart’s home. And so for me, as in much of life, it’s not what you know. It’s who. But I must add that trying to fry three two-minute eggs the way Paul Schaefer liked them—with NO cellophane edges!—could bring down more wrath than Marine boot camp. And don’t ever let Paul sleep too late on Sunday morning to make it to mass in nearby North Creek.

Paul Schaefer lived by letterheads. He had a double fistful over the years. I was born the same year as Paul’s letterhead group Friends of the Forest Preserve, formed in 1945 to fight the Black River Wars. I must now confess—with all due respect—that my siblings and I still often address each other as “Dear Friends of the Forest Preserve.” Today the official group is Adirondack Wild: Friends of the Forest Preserve.

When I first read James Glover’s A Wilderness Original: The Life of Bob Marshall it reminded me that the many family friends I grew up taking for granted as national conservation associates of my father Howard Zahniser had been recruited by New Yorker Bob Marshall in his travels. Bob Marshall’s cohorts and co-founders of The Wilderness Society included Benton MacKaye, Bernard Frank, Harvey Broome, Aldo Leopold, and Ernest Oberholtzer. They carried on his wilderness work as The Wilderness Society after Marshall died at age 38 in 1939.

MacKaye, Frank, and Leopold were trained foresters, as was Marshall, who also had a PhD in plant physiology. Broome was a lawyer for the Tennessee Valley Authority, where MacKaye and Frank worked as foresters. Also helping with Marshall’s early Wilderness Society work were his personal recruits Sigurd Olson, an advocate with Ernest Oberholtzer of today’s Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in Minnesota, and Olaus and Margaret E. “Mardy” Murie, who would play crucial roles in the creation of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Bob Marshall inspired wilderness advocacy not only for federal public lands but also for the Adirondack wilderness of his youthful summers at the Marshall family camp near Saranac Lake. In July 1932, three years before The Wilderness Society was organized, Bob Marshall ran into a young Paul Schaefer atop Mount Marcy. Schaefer was photographing ravages of forest fires caused by careless logging of Adirondack High Peaks forests above the elevations that loggers had assured Bob Marshall and others that they would not cut.

Paul Schaefer was doing what his conservation mentor John Apperson said we must do. Stand on the land you want to save. Take pictures so the public sees what is at stake. John Apperson’s rallying cry was “We Will Wake Them Up!” Paul would practice just that for more than a half century of wildlands advocacy. Atop Mount Marcy, not far above Verplanck Colvin’s Lake Tear of the Clouds, Bob Marshall captured Paul Schaefer’s wild imagination. Marshall called for wilderness advocates to band together, which took place with The Wilderness Society’s birth three years later, in 1935.

In 1946, 14 years after his peak experience with Bob Marshall, Paul Schaefer recruited our father Howard Zahniser to defend Adirondack forest preserve wilderness. Apperson and Schaefer showed their documentary film about the dam-building threats to western Adirondack forest preserve lands at the February 1946 North American Wildlife Conference in New York City. My father had gone to work for The Wilderness Society the previous September 1945. After their presentation, my father told Schaefer that The Wilderness Society would help defend the western Adirondacks against dams in what became known as the Black River Wars.

When they took up the gauntlet in 1946, to block the series of dams was universally deemed a lost cause. But Schaefer and Zahnie—as our father was known—went from town to town in western New York, testifying at public hearings, meeting with news people, and identifying and cultivating local advocates of wildlands.

Zahnie also brought national experts from Washington, D.C. to New York to testify against the dams. So Paul Schaefer was Zahnie’s mentor in sticking with lost causes, too. As Olaus Murie later said—and this is my all-time favorite quotation about our father—“Zahnie has unusual tenacity in lost causes.” That was a New York State skill. I hope you have that skill, too, “. . . unusual tenacity in lost causes.”

Schaefer invited Zahnie and our family to experience Adirondack wilderness firsthand that summer of 1946. Backpacking across the High Peaks wilderness that summer with Schaefer and his fellow conservationist Ed Richard, Zahnie remarked that the ‘forever wild’ clause of New York’s state constitution might well model the stronger protection needed for wilderness on federal public lands. The next summer, 1947, The Wilderness Society governing council voted to pursue some form of more permanent protection for wilderness. That 1947 vote set the stage for the 1964 Wilderness Act.

The administrative classifications that Bob Marshall and Aldo Leopold had won to protect wilderness on federal, national forests were proving ephemeral. A housing boom followed World War II’s end in 1945. Federal bureaucrats started de-classifying administratively designated wilderness areas for exploitation of timber, minerals, and hydropower.

Under Schaefer’s tutelage, Zahnie dove into the Black River Wars here in New York. Zahnie’s federal government public relations work had taught him the machinations of multi-media publicity. But from and with Paul Schaefer in the Adirondacks, Zahnie learned firsthand the art of grass roots organizing and stumping for wilderness. Paul Schaefer built a statewide coalition of hunters, anglers, and other conservationists and held it together by the strength of his personality for 50 or 60 years. If you’re looking for a job, there’s one that is probably going begging tonight.

This truths our calling the Adirondacks and Catskills “where wilderness preservation began.” The epic early 1950s fight against the Echo Park Dam proposed inside Dinosaur National Monument in Utah built the first-ever national conservation coalition. Then, having defeated the Echo Park dam proposal by 1955, Zahnie and the Sierra Club’s David Brower put that coalition to work for the legislation that would become the 1964 Wilderness Act.

Zahnie and David Brower, who then headed the Sierra Club, led the Echo Park Dam fight. Brower told Christine and me at the National Wilderness Conference in 1994 that Zahnie was his mentor in the practical technics of conservation advocacy. So this also puts David Brower in the direct line of mentoring by Bob Marshall and John Apperson and Paul Schaefer’s Adirondack wilderness advocacy. It was also during the western Adirondack dam fights that Zahnie met the philanthropist Edward Mallinkrodt, Jr., who helped bankroll the campaign against Echo Park Dam in the early 1950s.

In 1953 Zahnie gave a speech in Albany, New York to a committee of the New York State legislature. This was my father’s first major public formulation of the wilderness idea. His topic was the remarkable record of the people of the Empire State in preserving in perpetuity a great resource of wilderness on their public lands. The speech was titled “New York’s Forest Preserve and Our American Program for Wilderness.” The 1953 speech also included a sentence that, unfortunately, does not appear in the 1964 Wilderness Act. Zahnie told the legislators that “We must never forget that the essential character of wilderness is its wildness.”

Then, in 1957, Zahnie addressed the New York State Conservation Council’s convention in Albany. He titled this speech “Where Wilderness Preservation Began.” In it Zahnie said: “This recognition of the value of wilderness as wilderness is something with which you have long been familiar here in New York State. It was here that it first began to be applied to the preservation of areas as wilderness.” In August 1996 Dave Gibson and Ken Rimany, Paul Schaefer’s grandson David Greene, and my brother Matt Zahniser and I and our four sons backpacked across the High Peaks to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the 1946 trip made by Schaefer, Ed Richard, and Zahnie. It remains crucially important to speak clearly and strongly for this unparalleled legacy of wildness—here and nationally—that we love and cherish. And only astute wilderness stewardship can put the forever in a wilderness forever future.

Bob Marshall, who was Jewish, early fought for wilderness as a minority right. Marshall also fought for a fair shake for labor and other social justice issues. On his death at age 38 in 1939, one-third of Bob Marshall’s estate endowed The Wilderness Society, but two-thirds went to advocate labor and other social justice issues. Wilderness and wildness are necessity; they are not peripheral to a society holistically construed.

This bit of biography underscores how Congress declares the intent of the National Wilderness Preservation System Act to be “for the permanent good of the whole people…” —and this by a 1964 House of Representatives vote of 373 to 1. Isn’t that amazing? And by an earlier Senate vote of 78 to 12.

Wilderness and wildness are integral to what Wendell Berry calls the circumference of mystery. Wilderness and wildness are integral to what the poet Denise Levertov calls the Great Web. Wilderness and wildness are integral to what the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. calls our inescapable network of mutuality. Wilderness and wildness are integral to what God describes to Job as the “circle on the face of the deep,” to the bio-sphere, to our circle of life, to our full community of life on Earth that derives its existence from the Sun.

The prophetic call of wilderness is not to escape the world. The prophetic call of wilderness is to encounter the world’s essence. John Hay calls wilderness the “Earth’s immortal genius.” Gary Snyder calls wilderness the planetary intelligence. Wilderness calls us to renewed kinship with all of life. In Aldo Leopold’s words, we will enlarge the boundaries of the community—we will live out a land ethic—only as we feel ourselves a part of the same community.

By securing a national policy of restraint and humility toward natural conditions and wilderness character, the Wilderness Act offers a sociopolitical step toward a land ethic, toward enlarging the boundaries of the community.

Preserving wilderness and wildness is about recognizing the limitations of our desires and the limitations of our capabilities within nature. But nature really is this all-encompassing community—including humans—that Aldo Leopold characterized simply as “the land.” With preserving designated wilderness we are putting a small percentage of the land outside the scope of our trammeling influence.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Wilderness Act into law on September 3, 1964. Our mother Alice Zahniser stood in our father’s place at the White House signing, and President Johnson gave her one of the pens he used. The future of American wilderness lies in continued concerted advocacy by spirited people intent on seeing our visionary legacy of thinking—and feeling—about wilderness and wildness taken up by new generations. Howard Zahniser said that in preserving wilderness, we take some of the precious ecological heritage that has come down to us from the eternity of the past, and we have the boldness to project it into the eternity of the future. If you are looking for good work, you will find no better work than to be a conduit for those two eternities. Go forth, do good, tell the stories, and keep it wild.

Ed Zahniser recently retired as the senior writer and editor with the National Park Service Publications Group in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. He writes and lectures frequently about wilderness, wildlands, and conservation history topics. He is the youngest child of Alice (1918-2014) and Howard Zahniser (1906–1964). Ed’s father was the principal author and chief lobbyist for the Wilderness Act of 1964. Ed edited his father’s Adirondack writings in Where Wilderness Preservation Began: Adirondack Writings of Howard Zahniser, and also edited Daisy Mavis Dalaba Allen’s Ranger Bowback: An Adirondack farmer: a memoir of Hillmount Farms (Bakers Mills).

“The Wilderness Bill preserves for our posterity, for all time to come, 9 million acres of this vast continent in their original and unchanging beauty and wonder.” — President Lyndon B. Johnson, upon signing the Wilderness Act into law on September 3, 1964

50th Anniversary of the Wilderness Act

F ifty years ago today, on September 3, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Wilderness Act into law at a Rose Garden signing ceremony. This landmark law established the National Wilderness Preservation System, initially 54 Forest Service-administered areas that totaled 9.1 million acres. The Wilderness Act also provided, for the first time ever, protections for Wildernesses in the federal statutes, with the goal that wilderness designation would be permanent protection. The law, thanks to Howard Zahniser (the author of the Act), lyrically provided the legal definition of Wilderness, in part as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

ifty years ago today, on September 3, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Wilderness Act into law at a Rose Garden signing ceremony. This landmark law established the National Wilderness Preservation System, initially 54 Forest Service-administered areas that totaled 9.1 million acres. The Wilderness Act also provided, for the first time ever, protections for Wildernesses in the federal statutes, with the goal that wilderness designation would be permanent protection. The law, thanks to Howard Zahniser (the author of the Act), lyrically provided the legal definition of Wilderness, in part as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

The Wilderness Act also required that each additional area to be added to the National Wilderness Preservation System must do so through an Act of Congress. Since 1964, Congress has responded to the desires of the American public and expanded the wilderness system again and again. Today, the National Wilderness Preservation System has grown to 758 areas that total just under 110 million acres.

More detailed information on the Wilderness Act, its 50th anniversary, and Wilderness Watch’s own 25th anniversary will be found in the forthcoming issue of our print newsletter, the Summer/Fall issue of the Wilderness Watcher.

So today we celebrate with deep pride and great gratitude the people, like our own Stewart “Brandy” Brandborg, who struggled to pass the Wilderness Act for the eight long years it took, and for all those across the country who have fought to protect other areas that are now part of our magnificent National Wilderness Preservation System, areas that will be, in the words of the Wilderness Act, “an enduring resource of wilderness” for all generations.

So today we celebrate with deep pride and great gratitude the people, like our own Stewart “Brandy” Brandborg, who struggled to pass the Wilderness Act for the eight long years it took, and for all those across the country who have fought to protect other areas that are now part of our magnificent National Wilderness Preservation System, areas that will be, in the words of the Wilderness Act, “an enduring resource of wilderness” for all generations.

Happy Anniversary!

Photos:

TOP: On September 3, 1964, President Johnson signed the Wilderness Act into law. Standing behind him are many of the Congressional sponsors of the law. On the far right is Secretary of Interior Steward Udall. The 3rd from the right in the front row, with the dark-rimmed glasses and dark hair, is Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman. Only two women stand in the group, Alice Zahniser with black hair and Mardy Murie with grey hair. The President gave to each of them the pens that he used in signing the Wilderness Act into law; the husbands of each of these women (Howard Zahniser and Olaus Murie) had worked hard to write and pass the Wilderness Act but had died before that day. Photo by Abbie Rowe, courtesy of National Park Service, Harper’s Ferry Center, Historic Graphic Collection.

MIDDLE: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska. Photo by U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

BOTTOM: The Gila Wilderness in New Mexico, was one of the original Wildernesses designated by the Wilderness Act. Photo: Wikipedia.

Wilderness More Important than Ever

by Kevin Proescholdt and Howie Wolke

Christopher Solomon got it wrong in so many ways in his July 6 New York Times editorial, “Rethinking the Wild: The Wilderness Act Is Facing A Midlife Crisis”. The history of the wilderness movement and of the 1964 Wilderness Act shows how wrong and myopic he was. In fact, the visionary Wilderness Act is needed now more than ever.

Solomon bases his argument on a fundamental misunderstanding of the meaning and value of Wilderness. He argues that since all Wildernesses are affected by anthropogenic climate change, human manipulation of Wilderness is now acceptable — even desirable, since the genie is already out of the bottle. Intervene and manipulate without constraint, he proclaims. But this approach contradicts the very idea of Wilderness.

Mr. Solomon obviously confuses wildness with absolute pristine conditions. Congress never intended to set the bar so high that only entirely natural and pristine areas could qualify for Wilderness designation. Humanity’s global imprint is not new. Climate change is but the latest in a long history of human impacts to every corner of the planet, from smog and acid rain to habitat fragmentation and widespread human-caused extinctions.

A basic understanding of the Wilderness Act helps us understand the value of the uniquely American wilderness idea. A half-century ago, Congress defined Wilderness as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Untrammeled means un-manipulated or unconfined, requiring humility and restraint, to allow Wilderness to function without the heavy-handed human manipulations that characterize most of the world.

Human impacts have never disqualified areas from becoming Wilderness. But once Congress designates a Wilderness, manipulations and interventions must cease. Fortunately, there still remain large untrammeled landscapes where human impacts are “substantially unnoticeable” and where “wilderness character” dominates.

The Wilderness Act’s primary author was Howard Zahniser. His thoughts and writings are central to what the Wilderness Act means, and Solomon would benefit by studying them. Zahniser wrote, for example, that (unlike Solomon’s contention of the central importance of absolute pristine conditions) it is wildness that is central to Wilderness. “We must remember always that the essential quality of the wilderness is its wildness,” Zahniser explained, and his choice of “untrammeled” in the poetic definition of wilderness in the 1964 law was intended to protect that core character of wilderness.

Solomon also repeats the misconception that Zahniser and other Wilderness System founders never anticipated threats to Wilderness like climate change. On the contrary, Zahniser anticipated the very calls like Solomon’s for manipulating Wilderness when he wrote, “Such tracts should be managed so as to be left unmanaged.” And he defined wilderness as a place where human impacts are “substantially unnoticeable”, not entirely absent.

Change is constant in wild nature; Mr. Solomon is obviously unaware that wilderness enthusiasts have long acknowledged this. Once again, Howard Zahniser provided the needed guidance: “In the wilderness we should observe change and try not to create it!” Even though changes may occur in Wilderness that we humans may not like, the true test of our commitment to the Wilderness idea is to exercise that humility and restraint and eschew intervention.

Zahniser anticipated calls to manipulate Wilderness, even for seemingly beneficial-sounding reasons such as some of those Solomon proposed. That’s why Zahniser famously wrote, “With regard to areas of wilderness we should be guardians and not gardeners.”

So while modern human impacts certainly tempt us to try to “fix” whatever we perceive to be wrong or undesirable, let us not forget that such efforts often backfire, simply because nature is far more complex than we can perceive. And such efforts in wilderness would eliminate wildness and the contrast between wilderness and the rest of the planet.

On this increasingly human-dominated planet, un-manipulated wild Wilderness now has more value than ever. Solomon concludes that Wilderness manipulation is a “necessary apostasy to show how much we truly revere these wild places.” Yet if we follow his suggestions and manipulate the wildness out of Wilderness, there will be no wild places left. And that is exactly what the Wilderness Act guards against.

———-

Kevin Proescholdt is the Minnesota-based Conservation Director for Wilderness Watch, a national wilderness conservation organization. Howie Wolke co-owns Montana-based Big Wild Adventures and has been a wilderness guide/outfitter for 36 years. He is the current Vice President of Wilderness Watch. Each has been actively involved with wilderness conservation for over 40 years.

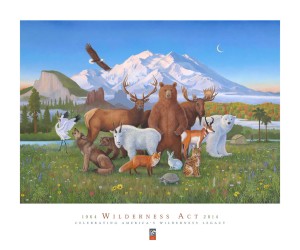

“The Peaceable Kingdom of Wilderness,” by internationally-acclaimed artist Monte Dolack, commemorates the Wilderness Act’s 50th anniversary and celebrates our 110 million-acre National Wilderness Preservation System, which spans ancient forests, vast arctic reaches, sweeping deserts, soaring mountains, remote coastal islands, and wild canoe country.

Wilderness Poster thoughts

“I worked through several ideas for this commissioned painting thinking about the important individuals who contributed to the idea of preserving Wild places. It is diverse and many people made this happen. I decided instead to focus on a rather formal portrait of some of the animals of our wild places with a backdrop of some of the wilderness areas across the United States. This painting for the 50th anniversary of the American Wilderness Act is about the interconnectedness of life and richness of landscape. All of our wilderness areas, though separated from each other physically are non-the-less connected, as is everything on this small planet spinning in space. The idea of the Peaceable Kingdom of Wilderness springs from Edwards Hicks’ 1820 Peaceable Kingdom which is folkloric in nature.

It is one of the best ideas we as a nation have ever had.”

Monte Dolack

5/23/14

Mr. Dolack was commissioned to create the original artwork and poster by Wilderness50, a group of non-profit organizations, academic institutions, and government agencies planning events around the country to commemorate the Wilderness Act’s 50th anniversary. Wilderness Watch has played a key role in Wilderness50’s planning efforts and recommended Mr. Dolack for this special project. Wilderness Watch worked closely with the artist throughout the process and is handling distribution of the posters.

Purchase a poster here: https://www.charity-pay.com/d/donation.asp?CID=75

By Susan Morgan and John Miles

On March 22, 2014 Polly Dyer received her honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters from Western Washington University in Bellingham, WA to recognize and celebrate her lifetime of conservation achievements.

On March 22, 2014 Polly Dyer received her honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters from Western Washington University in Bellingham, WA to recognize and celebrate her lifetime of conservation achievements.

Four years ago, after Polly’s 90th birthday party, The North Cascades Conservation Council reported that three hours of speakers stories hadn’t scratched the surface of her remarkable history. “The fruits of Polly’s leadership have blossomed wherever there is wilderness, from the Wilderness Act of 1964 through WA State’s three National Park Wilderness Areas and our various National Forest Wilderness Areas.”[i] Through six decades of championing wilderness, she has nurtured generations of wilderness supporters.

Polly would be the first to say that her life’s work began in 1945 when she met Johnny Dyer walking up a trail on Deer Mountain near Ketchikan AK. Sparks flew. They were engaged in six weeks and married four months later, and for the next 63 years, Johnny Dyer (“Climber, Sierra Club” pronounced the pin on his hat) fostered his wife’s activism and shared her passion for wilderness preservation.[ii]

The Dyers became a great team; no conservation task was too big or too small. Polly persuaded people to join the cause and served as mentor and model; the network she developed was vast and ranged from local activists to politicians, agency personnel and players on the national stage. She gained the respect of all and grew close to many.

Long-time wilderness advocate Karen Fant remembered going with Polly to the Mt. Rainier National Park Centennial. As they made their way to the car after the program, for more than two hours Polly joyously stopped to talk to dear old friends and associates with the Park Service, Forest Service, USFW, agency and conservation representatives. Karen concluded that she needed a leash or they would never get home. (Polly was driving.)[iii]

Though Washington became her home and center of operations, Polly’s scope is national. When she and Johnny lived for briefer times in the San Francisco area or on the East Coast, Polly organized Girls Scouts and together they started Sierra Club chapters and other organizations. Alaska remains one of her most treasured wild places. So moved by it’s natural beauty and scope, she called her life there “the basis for my whole life since.” In 1947, Johnny crafted leather saddlebags for her three-speed Schwinn, and Polly and friend Dixie shipped their bikes to Juneau where they picked them up and barged to Haines. As they biked toward Haines Junction, Canadian Mounties gave them a lift the last few miles into town. The Mounties also generously offered mattresses to the girls in a building that turned out to be the local jail. “There weren’t any hotels in those days,” Polly says. “Jail was easier than tent camping at that point. Then we biked on to Valdez to get more cash and finally to Anchorage.”[iv]

In 1953 the Dyers joined their friend David Brower and a host of conservation organizations in the historic fight against Echo Park Dam in Dinosaur National Monument. Wearing her hat as the conservation chair of the Mountaineers and another hat as a citizen activist, after a two-year skirmish, she and cooperators prevailed. Dinosaur was saved.

During that fight, Polly met Howard Zahniser, Executive Secretary of The Wilderness Society. Zahnie prepared the first draft of proposed wilderness legislation in 1956, and in 1957, Polly began working with Zahnie and other national, state, and local conservation groups. As they crafted language along the way, Polly suggested that Zahnie use the word untrammeled to “describe the character of the public lands that should be eligible for designation.”[v] After sixty-six versions, the act was finally passed in 1964 to establish the National Wilderness Preservation System and of course that little-used word was in it. Twenty years later she was at the center of the successful campaign to pass a Washington State Wilderness Act, which brought nineteen new wilderness areas into the national system.

In 1958 Polly organized a three-day hike along the coastline of the Olympic Peninsula with then U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas to increase public awareness about a planned portion of U.S. Highway 101. If constructed, the highway expansion would have destroyed what is now the 73-mile wilderness coastline of the Olympic National Forest. This successful hike now stand out in northwestern and National Park history.

Today, at 94, Polly moves more slowly but continues her work, primarily to “finish” North Cascades National Park. “I want to put my arms around wilderness” she says “and save it all.”[vi]

In 1967 Susan began her conservation career of twelve years with The Wilderness Society, and she subsequently worked with various conservation outfits (Earth First!, LightHawk, NM Environmental Coalition, Washington Wilderness Coalition, Forest Guardians, and others) that focused on wilderness, wildlands, and public lands conservation. Currently she is a copy editor and is president of The Rewilding Institute.

In 1967 Susan began her conservation career of twelve years with The Wilderness Society, and she subsequently worked with various conservation outfits (Earth First!, LightHawk, NM Environmental Coalition, Washington Wilderness Coalition, Forest Guardians, and others) that focused on wilderness, wildlands, and public lands conservation. Currently she is a copy editor and is president of The Rewilding Institute.

John is retiring after forty-six years as professor of environmental studies at Huxley College, Western Washington University. He is the author of several books on national park and wilderness history, and through these years in the Pacific Northwest has hiked, skied, and taught and studied the history of the North Cascades. He continues to write and plans much wilderness time in retirement.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Read more about the word “untrammeled” and its inclusion in the Wilderness Act in Kevin Proescholdt’s essay, “Untrammeled,” by clicking here.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[i] Olympic Park Associates, “Polly Dyer Chosen as Wilderness Hero,” Vol. 12, No. 1, Spring 2004

[ii] HistoryLink.org, The Seattle Times, August 7, 1974

[iii] Personal communication with Susan Morgan

[iv] Personal communication with Susan Morgan

[v] [v] Olympic Park Associates, “Polly Dyer Chosen as Wilderness Hero,” Vol 12, No. 1, Spring 2004, and personal communication with Susan Morgan

[vi] Personal communication with Susan Morgan

Cheering 50th Anniversary of Wilderness Act

By Michael Frome

Early in my career, when I was writing travel articles for various magazines and newspapers, I found myself reading the travel section of The New York Times every Sunday. The attraction for me was not in the stories about going places, but in a column called “Conservation,” in which the writer, John B. Oakes, expressed his lifelong concern for the environment.

Early in my career, when I was writing travel articles for various magazines and newspapers, I found myself reading the travel section of The New York Times every Sunday. The attraction for me was not in the stories about going places, but in a column called “Conservation,” in which the writer, John B. Oakes, expressed his lifelong concern for the environment.

In the edition of May 13, 1956 his conservation column commended new legislation introduced by Sen. Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota to establish a national wilderness preservation system. It was another step in the long political fight leading to passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964. That column impressed me as something I should know more about, and do something about too. It set me off on a path of identifying and celebrating wilderness wherever I found it, and now to cheer the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act in 2014.

But first a few words about John Oakes, who was a hero and friend of mine. His job at the Times initially was editor of Review of the Week; the conservation column was something he did on the side. Then, in 1961, he was named editor of the editorial page. For the next 15 years, until his retirement, Oakes editorialized about civil rights, the presidency, foreign affairs, politics and the environment, defining a lofty agenda of public policy. Even after retirement Oakes contributed powerful opinion pieces to the Op-Ed page (which he had started in 1970), including “Watt’s Very Wrong,” December 31, 1980, when James G. Watt’s nomination was pending in the Senate; “Japan, Swallow Hard and Stop Whaling,” January 19, 1983; and “Adirondack SOS,” October 29, 1988 (which elicited a letter to the editor of the Times from Gov. Mario Cuomo pledging renewed commitment to preserving the Adirondacks).

He was the kind of person I met and associated with in advocacy of the Wilderness Act. Another was Rep. John P. Saylor, a Pennsylvania Republican, who was the sole sponsor of the Wilderness Bill in the House. It was uphill all the way but he never gave up. “I cannot believe that the American people have become so crass, so dollar-minded and exploitation-conscious that they must develop every last bit of wilderness that still exists,” he declared on the floor of the House in 1961.

Meeting and knowing such people spurred me on to a new career leading to publication of “Battle for the Wilderness” in 1974. I found the Wilderness Act opened the way to a new level of citizen involvement and activism, a grass-roots conservation movement in which local people could be heard in behalf of wilderness areas they knew best.

In time I went to many different wilderness areas. I met with individuals and groups in many parts the country, observing the work that individuals do, rising above themselves and above institutions. I came to appreciate wilderness preservation as an idea that works, a manifestation of democracy, an expression through law of national ethics.

The American wilderness is many things to many people of our time: a sacred, spiritual place to the sheer idealist who persists in dreaming the old American dream; a laboratory of learning to the natural scientist; a test of hardihood to the outdoorsman and hunter; and rather an encumbrance on the land to the materialist whose modern view dictates that real estate must be used in order to be useful. I think that many scholars and educators would insist on speaking objectively with scientific rationale. But Aldo Leopold, even though equipped with the proper education and credentials, demonstrated emotion and aesthetic sensitivity as wholly compatible with science.

I met a different kind of people who showed ethical concern, a creative force in the battle for wilderness. They are legendary. Olaus Murie was already gone, but his wife, Margaret, or “Mardy,” and I became lasting friends. She had been with Olaus on his pioneering surveys and research in Alaska and elsewhere for the Biological Survey (later the Fish and Wildlife Service) until he left the government to be free of its restraints. And she had been with him in the epochal 1956 expedition that led to establishment of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, embracing the largest mountains of the Brooks Range and their foothills sloping north to the coastal plain and southward toward the Yukon River as a book the way God made it.

Olaus was a leader of the Wilderness Society from its incorporation in 1937 until his death in 1963. In addition to extensive technical and popular writing, he executed many exceptional paintings of animals as he saw them in the wild. His strength, like the strength of Aldo Leopold, Howard Zahniser and the others derived from more than admiration of nature, but from the desire to save nature through personal involvement.

The Wilderness Act, however, stimulates a fundamental and older tradition of relationship with resources themselves. A river is accorded its right to exist because it is a river, rather than for any utilitarian service. Through appreciation of wilderness, I perceive the true role of the river as a living symbol of all the life it sustains and nourishes, and my responsibility to it.

Wilderness is friendly, not forbidding. Now that experts have so many plans for its disposition, enlightened use, enthusiasm and appreciation will help place it in proper perspective. Best of all, perhaps, is that wilderness is endowed with the absence of artificial noises, the absence of artificiality and a tremendous store of basic nourishing reality.

Land use embodies both science and philosophy, but the philosophy is more important by far. It must come first, based on love of the earth and respect for all creatures with which we share it. How to utilize wilderness, and public lands in general, as an educational and inspirational resource so that upcoming generations respect the natural world, is part of the fundamental challenge as we look ahead to the next 25 years and beyond.

We need to learn much more about wilderness: where it is and where it was; its physical and psychic therapeutic qualities; its relation to science, art, ethics, and religion; the contributions of individuals who have helped, in their own way, to save it and give meaning to it for society.

No other country is so enriched by its parks, forests, wildlife refuges and other reserved administered by towns, cities, counties, states and the federal government. Land is wealth, and we the people ought to hold onto every acre of it in the common interest. Public lands provide roving room, a sense of freedom and release from urbanized high-tech super-civilization. Without public lands there would be no place of substance left for wildlife, which has shared our heritage since time immemorial.

Americans should be proud of the many millions of acres safeguarded by the Wilderness Act, for wilderness preservation treats ecology as the economics of nature, in a manner directly related to the economics of humankind. Keeping biotic diversity alive is the surest means of keeping humanity alive. But conservation transcends economics—it illuminates the human condition by refusing to put a price tag on the priceless.

Michael Frome, Ph.D., has pursued an illustrious career as author, educator and tireless guardian of the environmental commons. Former Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin declared in Congress: “No writer in America has more persistently and effectively argued for the need of national ethics of environmental stewardship than Michael Frome. ” Michael has been a member of Wilderness Watch’s board of directors or advisory council for nearly 20 years.

Of Wolves and Wilderness

Of Wolves and Wilderness

By George Nickas

“One of the most insidious invasions of wilderness is via predator control.” – Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

Right before the holidays last December, an anonymous caller alerted Wilderness Watch that the Forest Service (FS) had approved the use of one of its cabins deep in the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness (FC-RONRW) as a base camp for an Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) hunter-trapper. The cabin would support the hired trapper’s effort to exterminate two entire wolf packs in the Wilderness. The wolves, known as the Golden Creek and Monumental Creek packs, were targeted at the behest of commercial outfitters and recreational hunters who think the wolves are eating too many of “their” elk.

Idaho’s antipathy toward wolves and Wilderness comes as no surprise to anyone who has worked to protect either in Idaho. But the Forest Service’s support and encouragement for the State’s deplorable actions were particularly disappointing. Mind you, these are the same Forest Service Region 4 officials who, only a year or two ago, approved IDFG’s request to land helicopters in this same Wilderness to capture and collar every wolf pack, using the justification that understanding the natural behavior of the wolf population was essential to protecting them and preserving the area’s wilderness character. Now, somehow, exterminating those same wolves is apparently also critical to preserving the area’s wilderness character. The only consistency here is the FS and IDFG have teamed up to do everything possible to destroy the Wilderness and wildlife they are required to protect.

Middle Fork Salmon River, Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness, Idaho: Where nine wolves were killed by IDFG’s hired hunter-trapper. Photo: Rex Parker

Wilderness Watch, along with Defenders of Wildlife, Western Watersheds Project, Center for Biological Diversity, and Idaho wildlife advocate Ralph Maughan, filed suit in federal court against the Forest Service and IDFG to stop the wolf slaughter. Our suit alleges the FS failed to follow its own required procedures before authorizing IDFG’s hunter-trapper to use a FS cabin as a base for his wolf extermination efforts, and that the program violates the agency’s responsibility under the 1964 Wilderness Act to preserve the area’s wilderness character, of which the wolves are an integral part. Trying to limit the number of wolves in Wilderness makes no more sense than limiting the number of ponderosa pine, huckleberry bushes, rocks, or rainfall. An untrammeled Wilderness will set its own balance.

The FS’s anemic defense is that it didn’t authorize the killing, therefore there is no reviewable decision for the court to overturn, and that it was still discussing the program with IDFG (while the trapper was in the field killing the wolves). Unfortunately, the district judge sided with the FS and IDFG, so we filed an appeal with the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Rather than defend its action before the higher court, Idaho informed the court that it was pulling the trapper out of the Wilderness and would cease the program for this year. In the meantime, nine wolves are needlessly dead.

We will continue to pursue our challenge because the killing program will undoubtedly return. The Forest Service can’t and shouldn’t hide behind the old canard that “the states manage wildlife.” Congress has charged the FS with preserving the area’s wilderness character and the Supreme Court has held many times that the agency has the authority to interject itself in wildlife management programs to preserve the people’s interest in these lands. Turning a blind-eye is a shameful response for an agency that used to claim the leadership mantle in wilderness stewardship.

Wilderness Watch expresses its deep appreciation to Tim Preso and his colleagues at Earthjustice for waging a stellar legal battle on our behalf and in defense of these wilderness wolves.

George Nickas is the executive director of Wilderness Watch. George joined Wilderness Watch as our policy coordinator in 1996. Prior to Wilderness Watch, George served 11 years as a natural resource specialist and assistant coordinator for the Utah Wilderness Association. George is regularly invited to make presentations at national wilderness conferences, agency training sessions, and other gatherings where wilderness protection is discussed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.