By Brett Haverstick

Taking a long trip into the backcountry during winter doesn’t appeal to some people. That’s understandable. But I enjoy it, and it’s something I try to do a few times a year. Winter backpacking is very different, and more challenging, compared to strapping on the pack during other seasons.

For one it’s darn cold, with many trips never getting above freezing, day or night. Two, there’s usually lots of snow on the ground, which means you’re probably wearing snowshoes, and, perhaps, breaking trail too. Three, your pack is heavier because of all the extra warm gear you are carrying, including more food because you need to consume a lot of calories each day. Four, you have to work harder in just about everything you do, from setting up your shelter and trying to stay warm to melting water and attempting to stay hydrated. Five, there’s not a lot of daylight, so you have to stay motivated and keep moving if you want to cover some miles. Lastly, not too many people want to spend 5-6 days in the cold, blowing snow of the northern Rockies in January! But find someone to share the workload if you can!

My recent trip into the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness was with a friend, and, perhaps more importantly, an individual with a skill set that I could trust and depend on. Once the weather report showed a high-pressure system moving across the region, Russell and I finalized our plans and set out for the trailhead. We felt confident we could cover 50 miles before the next weather front moved in.

For two and a half days, we trudged across the frozen ridge, one foot after the other, breaking snow almost the entire time. Occasionally, we would hear the call of the raven or the knock of the woodpecker, but for the most part we walked in silence and deep in thought. Accompanying us the whole time was a set of moose tracks, with deer and elk tracks scattered about. It appeared snowshoe hare were in the area too. Blood on the trail indicated that a mountain lion, or another carnivore, might have wounded one of the ungulates.

The daily routine of building the morning fire, boiling water, drying gear, packing up, snowshoeing 10-16 miles, and then searching for a place to dig out the next snow cave was in some ways more mentally challenging than physical. But the white silence of the forest was peaceful, views of the snow-covered mountain peaks were tantalizing, and the cold, crisp air was exhilarating. With each arduous step, the wilderness boundary drew nearer.

You know the feeling. As one travels down the trail, through the forest, around the next bend or over the saddle, your heart pounds like a kid at Christmas. You anxiously await the sign that reads “…Wilderness, “…National Forest.” Yes, you say to yourself. Hope for humanity. Escape from the madness. Refuge for the plants and animals. Nature’s Bill of Rights at last. Leave me here and let me die with my true friends! And down the trail you continue.

Prior to our trip departure, Russell and I learned about the intent of the Idaho Fish & Game Department to land helicopters, and harass and collar elk, in the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness. We were angry, concerned, disappointed, and flabbergasted by the fact that the Forest Service gave the green light to land machines in the Wilderness, up to 120 times over a 3-month period. Of course, it doesn’t matter if it’s 1 time or 12 times, but 120 times was mind-blowing. Who the hell is running the Forest Service? Didn’t they, along with millions of Americans, just celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Wilderness Act not too long ago? Looks like that was lip service!

And what about the people running the Idaho Fish & Game Department? Why do they still have authority over wildlife management on federal public lands? Why are their intensive and intrusive management plans being permitted in federally designated Wilderness? When is that going to change? Why is the Forest Service continually shining the shoes of the state hook and bullet departments? Who is really administering the Wilderness?

As Russell and I descended in elevation on the third day, the sun shined warmly, the skies stretched a bright blue, and the mighty Salmon River came within view. We peered though the binoculars, and combed the south-facing slopes for herds of elk. Dozens of ungulates lay basking on the hills, while those closer leaped and bound to a more secure place. We also observed whitetail and mule deer (strangely enough together) and lots of wolf tracks. Far off in the distance, we saw what looked like two golden eagles circling a spot on the hill, as if a kill had recently occurred.

Despite seeing a number of horses by the river late that afternoon (why are horses running freely on the national forest in winter, particularly in crucial winter-range habitat?), not a human was in sight, and the frozen riverbank was ours to explore and make home. We rested and dreamily watched small pieces of ice float downstream along the sides of the quiet, rolling river.

Later that evening, after a hot meal, warm fire, and the usual time-to-get hydrated routine, we dozed peacefully under a star-studded sky when suddenly we were awoken by the yips, screams, and howls of coyotes. After shaking our heads no, those are not wolves, we gleefully listened to the songs (and celebrations?) of a dozen coyotes not far from our tarp. They yipped for 3-4 minutes but it felt like a lot longer than that. The sweet music of the Wilderness had finally reached us!

When day broke and our bags were packed, Russell and I contemplated where the Idaho Fish & Game helicopters could be. Were they invading to the south along Big Creek? Were they harassing and stressing dozens of cows and calves to the east? The mere thought of these non-conforming, highly mechanized machines flying and landing wherever they want in the Wilderness made us sick to our stomachs. We both wanted to know how can the uses of helicopters, net-guns, tranquilizers, and GPS-collars be the minimal tool(s) needed to administer the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness? None of it made any sense. Little did we know that wolves were being collared too.

Which leads me to my final thoughts. What good is a National Wilderness Preservation System if the federal officials charged with administering the system, and individual areas, continues to approve projects that are incompatible with the Wilderness Act? Why are the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service repeatedly rubber-stamping proposals that harm Wilderness? How is the collaring of wildlife in federally designated wilderness representative of a self-willed landscape? Explain to me how helicopters, net-guns, and radio-collars enhance or preserve wilderness character?

This tragedy (“accident”) should serve as a lightning rod to spark a discussion, better yet, a movement, to do two things: create an independent federal department solely charged with stewardship of the wilderness system, and pressure Congress to pass legislation that forbids all state fish and game agencies from conducting any operations inside federally designated Wilderness.

To hell with the Forest Service and the other federal agencies, which continue to trammel the Wilderness and our natural heritage. We cannot keep leaving it to the attorneys to defend the Wilderness Act. We must do something bold. The status quo is badly broken and only getting worse. Ed Abbey is rolling in his grave and still screaming, “The Idea of wilderness needs no defense, just defenders.” This message needs to reach every living room in America.

Brett Haverstick is the Education & Outreach Director for Friends of the Clearwater, a public lands advocacy group based in Moscow, Idaho. He has a B.S. in Parks & Recreation Management from Northern Arizona University and a Master’s degree in Natural Resources from the University of Idaho. He has been a member of Wilderness Watch since 2007. The views expressed are his own.

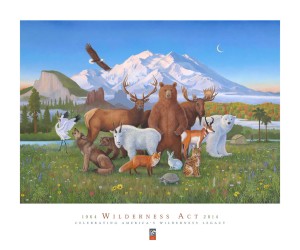

ifty years ago today, on September 3, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Wilderness Act into law at a Rose Garden signing ceremony. This landmark law established the National Wilderness Preservation System, initially 54 Forest Service-administered areas that totaled 9.1 million acres. The Wilderness Act also provided, for the first time ever, protections for Wildernesses in the federal statutes, with the goal that wilderness designation would be permanent protection. The law, thanks to Howard Zahniser (the author of the Act), lyrically provided the legal definition of Wilderness, in part as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

ifty years ago today, on September 3, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Wilderness Act into law at a Rose Garden signing ceremony. This landmark law established the National Wilderness Preservation System, initially 54 Forest Service-administered areas that totaled 9.1 million acres. The Wilderness Act also provided, for the first time ever, protections for Wildernesses in the federal statutes, with the goal that wilderness designation would be permanent protection. The law, thanks to Howard Zahniser (the author of the Act), lyrically provided the legal definition of Wilderness, in part as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” So today we celebrate with deep pride and great gratitude the people, like our own

So today we celebrate with deep pride and great gratitude the people, like our own

You must be logged in to post a comment.